Posted by TOKYO MATCHA SELECTION - Foreign staff (living in Japan) on 24th Jun 2017

* Kyusu tea pot & 2 Yunomi tea cups set

My mother, Dolly, was raised in an area of Staffordshire commonly known as the Potteries, famed, as you may know, for its fine earthenware. From the 17th century on, names like Wedgwood, Royal Doulton, Minton, Spode and Dudson had become synonymous with English ceramics, particularly bone china and creamware, and of which, Dolly was an ardent collector.

Thus, I grew up in a home dominated by teapots and tea sets, all lovingly displayed in glass cabinets or on sideboards; an ever-present physical reminder of Dolly's nostalgia for her home town. And with my father working in the then still flourishing Nottingham lace industry, there was never a shortage of doilies and runners on which to exhibit Dolly's collection, especially in the room we used to receive visitors. This wasn't simple ostentation, nor was it ever disorderly, but every available space was filled with the kind of cluttered sentimentality that I've spent my entire adult life trying to avoid.

Japanese Aesthetics

I'm not going to tell you that Japanese homes don't have clutter, because they do; because all human beings have a need for nostalgia and sentimentality when they reach a certain age. Yet I've visited few Japanese houses that didn't have at least one special space that was defined as much by its lack of content, than by what was placed there.

Often, this will be a simple tokonoma, or alcove - a space of profoundly stark and subtle, even abstract, silence; wherein the beauty and transience of nature is not so much celebrated, as observed with quiet grace through mindful placement of objects; shodo scrolls, flower arrangements, a simple earthenware vase. The simple, the "imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete" are hallmarks of the Japanese aesthetic known as wabi-sabi, ideals that grew out of Buddhist teachings.

Hagi Ware

Wabi-sabi is fairly well-known in the West, but often misunderstood as a philosophy. Actually, its aesthetic ideals are regarded as part and parcel of the fabric of life in Japan. With its emphasis on qualities of simplicity, modesty, austerity, asymmetry and roughness, it is perhaps not surprising to find the wabi-sabi aesthetic expressed through at least some traditional styles of Japanese pottery.

In the tea ceremony, the ceramics used are often very simple and rustic-looking, both lacking perfect symmetry, and finished in a course and unworked style. The colours of items often change over time with repeated contact with hot water, and tea bowls are never discarded just because they become chipped at the bottom; perhaps one accepts the change in texture as inevitable.

The best-known pottery of this type is hagi-yaki, or Hagi ware, from the town of Hagi in Yamaguchi prefecture, a style originally brought to Japan by Korean potters in the 16th century. Sadly, many such potters were abducted to Japan after its later conquest of Korea. However, to this day, many traditional tea ceremony performers and tea houses favour Hagi ware pottery, whilst some prefer decorative porcelain.

Kyushu Porcelain

In the mid 17th century, following the collapse of the Ming dynasty and the turmoil that followed, Japan became the major exporter of porcelain to Europe, providing a variety of styles using mostly traditional Chinese designs. Arita-yaki, or Arita ware, comes from Kyushu, and is thought to have been first developed by a Korean potter, Yi Sam-pyeong. However, porcelain had been produced in the Arita area since the late 16th century, when porcelain clay was discovered there, so there were already kilns operating in the area by Yi Sam-pyeong's time.

But Kyushu had also become home to many Chinese refugees, and they probably brought the technique of overglaze enamel colouring to Arita. This led to the decorative kakiemon style, characterised by beautiful depictions of nature or dramatic landscapes, and rendered in rich, vivid hues of red, blue, green, yellow and purple. The technique was designated an Important Intangible Cultural Property by the Japanese government in 1971.

But not all Arita ware was an imitation of Chinese or Korean designs; Nabeshima-yaki, or Nabeshima ware, which was first produced around 1700, drew on purely traditional Japanese designs, particularly those common to woven fabrics, and included many abstract elements as well as the use of 'empty' space.

I had asked my good friend, Tetsuko-san, herself a tea ceremony performer, where the best pottery was produced, but she said there were so many kilns throughout Japan that to say which was, or had been the best at any given time was difficult, but I'm indebted to her for pointing me towards Hagi and Kyushu for inspiration. They're all among her favourite styles, and I know she's very particular abut the pottery her guests handle.

Handling the Tea Cup

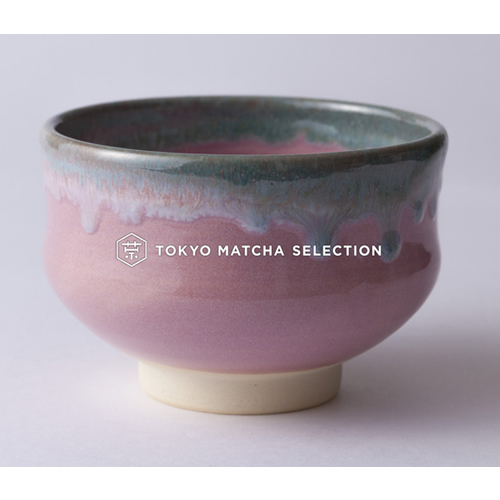

*Kyoto Pottery Matcha Bowl : Pink Oribe

Tea ceremony guests or participants are encouraged to appreciate the tea bowl or cup after it has been passed around, paying careful attention to the design, the glaze and the 'feel' of the pottery, perhaps even identifying its origins; for tea ceremony aficionados, it is a well-loved part of the ceremony. Tetsuko-san tells me that some people believe they discover something of themselves in the tea cup, something baked in the clay.

But then, taken together, all the procedural and aesthetic elements of the tea ceremony do seem to act on one's consciousness, altering it in subtle, almost imperceptible ways. And the really strange thing is, that when you've done that during the tea ceremony, when you've put your attention into a vessel, you find yourself doing it in everyday life too; so even the chip on the lip of one's favourite coffee mug suddenly feels different, somehow both familiar and inevitable; a thing in use, yet already in decay.